ond wave of COVID-19 cases surged across the country and in Colorado this

summer, mental health professionals saw another crisis: More people seeking help and not enough resources.

Even before the new coronavirus infected the U.S., county by county, experts say there weren’t enough mental health workers to meet needs, but stress and isolation due to the virus have intensified an existing quagmire.

It has also presented new opportunities, such as reaching more patients virtually, and led to relaxed regulations that make it easier for trained professionals to reach people.

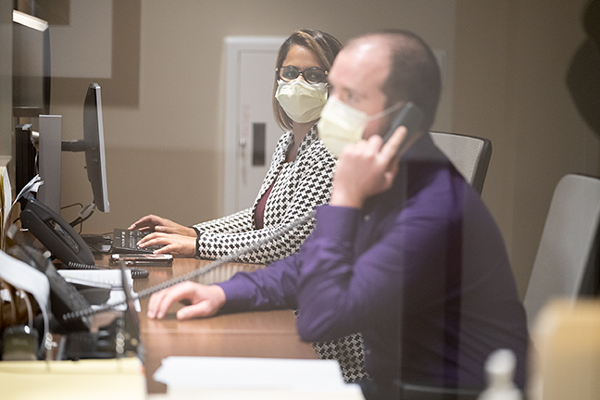

Photo by PHILIP B. POSTON/Sentinel Colorado

Accessing Care

Psychiatry residents at the HealthONE Behavioral Health and Wellness Center in Aurora have seen firsthand how COVID-19 has turned the health care industry, specifically mental health care, upside down in a matter of weeks.

“When COVID-19 came around we didn’t want to have people coming into the office to increase their risk, so we actually got telemedicine started off pretty, pretty quickly,” said Dr. Geoffry Harris, a fourth year resident at the hospital who previously saw lots of patients in person. “It’s one of those things where we can’t believe it. I think it may have changed outpatient work for probably forever. You can’t really unring that bell.”

That could be good news for people across the country in both urban and rural areas. About half of Colorado counties, all of them outside of the Denver metro region, don’t have a practicing psychiatrist, but with

tele-medicince, accessing that care becomes much easier.

“I think in some ways there are a few blessings in disguise that came out of COVID-19. Very few, but there are a few. One of them is the increased use of tele-psychiatry, so the increased use of technology to be able to see psychiatric patients who are remote. That technology has existed for more than 20 years,” said Dr. Patricia Westmoreland, the residency program director at the HealthONE center.

Westmoreland did her psychiatry training in Iowa, which she says seemed to adapt quickly to virtual visits long before the pandemic because so many regions are rural.

“Unfortunately, I think throughout the country there has traditionally been some reticence to embrace that technology because people feel it’s not as good as the real thing. It’s not as good as seeing people in person,” she said. “Well, COVID-19 changed that very quickly, and I think we all learned with COVID-19 that you’re going to have to learn to do Zoom meetings, you’re going to have to do Zoom lectures. Even if you were not somebody who was crazy about talking to people over TV, you better get familiar with it because even people in practice in Denver, for example, have very quickly turned their practices to tele-psychiatry, and I’m hoping that that will be a boon for the rural areas.”

Because of the virus, many people who would have previously visited their doctor in-person don’t feel comfortable to do so right now. 43% of respondents in a recent DocASAP questionnaire said that they wouldn’t feel comfortable going back to see a healthcare provider in person until at least the fall.

While healthcare facilities are traditionally thought of as sterile environments, this perception has been negatively impacted during the pandemic, according to the survey. When asked, “right now, which of the following facilities do you feel are safest to enter,” 42% of respondents selected a grocery store. 32% said a hospital and 26% said a doctor’s office. 12% said urgent care centers were safest to enter, just below public transit and airplanes at 13%.

Increased Need

In April, as most of the country was under some sort of stay-at-home order, mental health experts started raising red flags about an impending mental health crisis.

“You can’t put people into situations where they’re locked in their homes for weeks on end and not expect that there’s going to a significant number of people that develop mental health problems,” said Elinore McCance-Katz, who leads the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

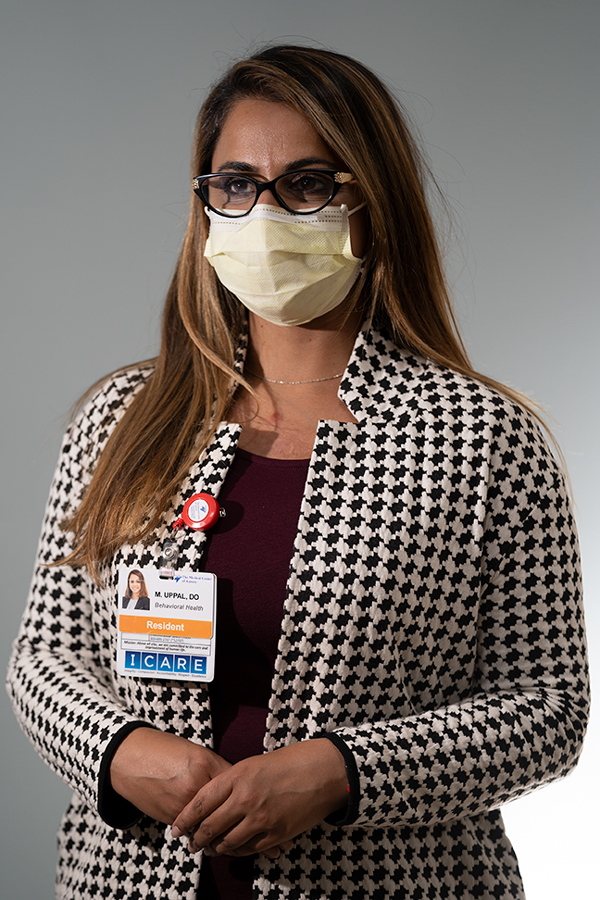

Photo by PHILIP B. POSTON/Sentinel Colorado

Locally, the story was much the same. Dr. Anne Garrett-Mills, chief medical officer at Aurora Mental Health, told the Sentinel in April there was an uptick in people seeking services.

Part of that has been the stress of the pandemic itself, but also because more people are looking for services who otherwise might seek help somewhere else, like schools and universities.

“Human beings are under stress and that is apparent in our meetings,” she said.

There’s also been an uptick in a need for substance abuse resources.

“If you have been struggling with mental health, now you are but maybe with grief and anxiety, too,” she said. “Some people are falling back to old coping mechanisms and substance abuse is more of a problem that it might be otherwise.”

Residents at the 120-bed HealthONE Behavioral Health and Wellness Center, a psychiatric hospital, in Aurora say they’ve been seeing much of the same, and treatment can be a little trickier when working with patients virtually. Doctors must be much more diligent when prescribing medications, especially ones that come with serious side effects.

That means even more education for patients.

“In a situation like this, when there is telemedicine psychoeducation becomes very important. It already is, but spending those few extra minutes to educate our patients, especially with side effects,” said Dr. Monica Uppal, a second year resident. “And also yes, it does get difficult to get them to go get their labs drawn or go see their primary care physician. So, in situations like this, and especially during (the pandemic), I’ve seen myself just providing a lot more psychoeducation because I know, again, getting to the doctor’s office is much more difficult.”

Aurora Mental Health has added and bolstered more services in the wake of the pandemic. A new hotline equipped with therapists is now live for residents and Connect Aurora helps people maneuver the insurance process if they’ve recently lost a job.

Like Denver, Aurora Mental Health was hoping to ask voters for a tax increase to fund mental health services for the community, but the ballot question was postponed due to the pandemic.

Turning the Corner

Despite the challenges mental health care workers are facing in unprecedented times, there’s a sense that there is a shift in how Americans are approaching the topic.

Vincent Atchity, president and CEO for Mental Health Colorado, said it seems like COVID-19 has forced more people to have conversations about mental health.

“For the longest time I’ve been trying to teach people to understand we do ourselves a disservice by talking about mental health versus physical health and that it affects some subset of people,” he said. “The two are totally intertwined.”

Perhaps it’s the isolation that’s forced the conversation or that the pandemic has turned so many things upside down that “hey, how are you doing?” is no longer a sort of throw away line, Atchity said.

People aren’t really saying “good” and just moving on with the conversation. That in itself is progress.

Fewer than half of Americans with mental illness reported getting help in the past year,

Photo by PHILIP B. POSTON/Sentinel Colorado

according to a federal survey. Among the big barriers are costs and a shortage of providers.

At clinics that offer free or low-cost therapy, wait lists often stretch for weeks in normal times. And getting treatment can be just as difficult, or even harder, for people who earn too much to qualify for state help, yet still struggle to get by.

Relaxing some regulations, such as allowing providers to work across state lines, has created more access, experts like Westmoreland and Atchity say. That’ll continue to make a difference in the future.

The HealthONE residents and Atchity alike say this historic event could be a big moment for advocacy of services, despite there being a budget crisis at the local and state level.

“In times like these, we do kind of learn what services our patients would benefit from, and how we can encourage politicians to perhaps grab more funding for certain types of programs and what we can do to support our community,” Upall said.

— The Associated Press contributed to this report